A Q&A with Dr. Piedad Urdinola Contreras is the Director of Colombia’s national statistics office, the Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadisticas (DANE).

Civil Registration and Vital Statistics (CRVS) is the continuous, universal, timely, inclusive and compulsory recording of births, deaths and causes of death in the population. In most countries, the registration of a birth creates a person’s legal identity, which is the key to unlocking access to services, rights and protections that are otherwise out of reach to the unregistered. In addition, civil registration data forms the basis for essential vital statistics for use in policy, planning, and monitoring and evaluation of health and social policy.

Dr. Piedad Urdinola Contreras is the Director of Colombia’s national statistics office, the Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadisticas (DANE). In recent years, DANE has worked closely with the civil registry and the ministry of health to implement innovative approaches to strengthening registration of births and deaths, particularly with Black and Indigenous communities in areas with difficult access to government services. As both an economist and demographer, Dr. Urdinola brings a unique perspective to the table. We talked with her about the remarkable ways that data are used in Colombia, and what other countries can learn from Colombia’s model.

How can birth and death registration influence public policies in Colombia, particularly for undercounted and hard-to-reach groups?

A civil registration and vital statistics system serves as a legal instrument, a demographic instrument, and as a public health instrument.

As a legal instrument, birth registration confers a legal identity, and the rights associated with that identity, to an individual. As a demographic instrument, death registration helps policymakers understand who in a population is dying, and from what. As far as public health goes, we only have to look back to the COVID-19 pandemic to see how powerful of a tool epidemiological surveillance was for the provision of fundamental health services.

Health systems rely on demographic data to function. We need to know how fertility trends and mortality trends are changing, projections about the population’s growth, and information on changes in demographic structures for particular groups.

DANE has used innovative methods to strengthen the registration of births and deaths in the population, with a particular focus on people who are more challenging to access, such as Indigenous groups and communities that are far from urban centers. Why have these efforts been so important for DANE?

Every country needs to have data on its population, and acquiring data on hard-to-reach communities is especially important. Without a full picture, we can’t answer some of the most fundamental questions for our country’s policy planning.

In 2021, we developed a strategy in collaboration with undercounted ethnic groups, such as communities living in the department of Amazonas, to increase the number of births and deaths registered across the country. By successfully navigating various cultural barriers, including different languages, we were able to give the state a broader vision of our population diversity and make it possible to create more inclusive and participatory public policies. Since then, we have maintained a direct relationship with these communities, which has helped us to further improve and strengthen their records.

We know that DANE has positioned itself in the country as an entity that different stakeholders, from technicians to academics to decision-makers, can consult. How does fulfilling this role affect the way in which DANE disseminates data?

We are seeing a lot more interest, especially from the younger generations, in statistics and data. The digital age has brought forth both opportunities and new challenges, and we work to adapt to these new demands for information and understand the characteristics of our users. Knowing this, we have an advisory committee of experts to guide us in our dissemination efforts.

Involving the academic world has been an important strategy, not only because they advise us, but also because they help us disseminate our work within academia. In addition, the presentations we make at press conferences, and our practice of providing information and consultation alike on a digital platform, allow us to educate the general public.

Colombia is unique in the breadth of data that is publicly available. Why has the government made the decision to have open and public data, and what lessons can other countries learn from DANE’s experience contributing to this mission?

I think the government’s decision to have open and public data is in line with what is happening all over the world. We are witnessing a global movement toward more information sharing and open data. On our side, we no longer only publish just tabulations and summary data, but also microdata, making more information available to more users, citizens and academics alike. When they access this data, these experts become interconnected with peers from other countries. They begin to compare data across the globe, improving the quality of analysis overall. I truly believe that any country that wants to continue to evolve in the dissemination of information has to follow this path of opening up information.

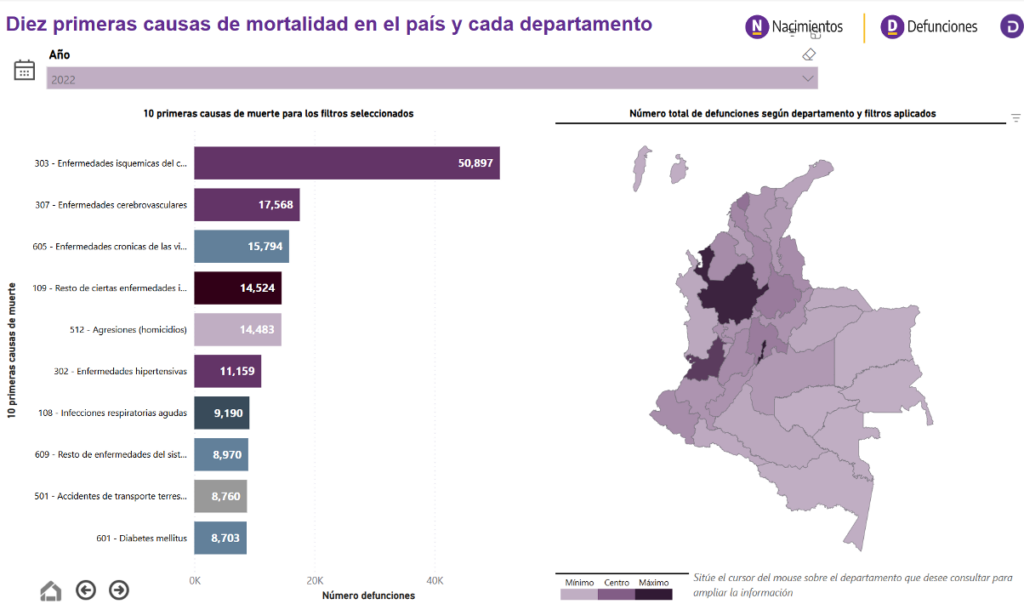

Click here to view the DANE dashboard.

What are some key lessons that other countries can learn from Colombia in the publication and use of vital statistics?

It is critical to convene multiple stakeholders to collaborate together. We invite academic experts and public policy decision-makers to participate in the dissemination of our work, whether on a new methodology or product. We hold panels at the end of the press conferences and find that this makes the figures and data clearer and more concrete to policymakers, so they are better able to use the data for its true purpose, which is decision-making for better public health outcomes.

It is deeply important to aim for harmonized and collaborative work among different institutions, especially in the area of vital statistics, where there are almost always three or four institutions involved.

We also have to collaborate with the communities themselves, particularly those that are undercounted or hard-to-reach. Although this is possible, it is very difficult to achieve from a central level. Working with the grassroots communities was an important lesson for us, particularly to overcome the obstacles presented by varying cultural differences.

And last but not least, having open data and open methodologies is very useful for transparency. It generates trust with the users, technicians, the academic community, and society in general, and enables these stakeholders to give us crucial feedback to strengthen our practices.

About the Bloomberg Philanthropies Data for Health Initiative

Today, approximately half of all deaths in the world go unrecorded; accordingly, health policy decisions are often based on inadequate information. Data for Health, funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies and the Gates Foundation, partners with low- and middle-income countries to improve public health data and use of data for policymaking. To learn more, visit: https://www.bloomberg.org/